User-defined functions¶

Introduction¶

There is still a lot of duplicated code — the actual drawing of the rectangle — around. If you need to copy and paste code, that is usually a sign of lacking abstractions. (Programmers call it a code smell.)

Functions are one way to express abstractions in Python. Let’s take turtle.reset() for example. It is actually an abstraction for a number of steps, namely:

- Erase the drawing board.

- Set the width and color back to default.

- Move the turtle back to its initial position.

A function can be defined with the def keyword in Python:

def line_without_moving():

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.backward(50)

This function we defined is called line_without_moving and it is an abstraction for two turtle steps - a move forward and a move backward.

To use it (or as it is usually called, “to call it”), write its name followed by parentheses:

line_without_moving()

turtle.right(90)

line_without_moving()

turtle.right(90)

line_without_moving()

turtle.right(90)

line_without_moving()

We could write more functions to remove some of the repetition:

def star_arm():

line_without_moving()

turtle.right(360 / 5)

def star():

star_arm()

star_arm()

star_arm()

star_arm()

star_arm()

Important

Python uses indenting with whitespace to identify blocks of code that belong together. In Python a block (like the function definitions shown above) is introduced with a colon at the end of the line and subsequent commands are indented — usually 4 spaces further in. The block ends with the first line that isn’t indented.

This is different to many other programming languages, which use special characters (like curly braces {}) to group blocks of code together.

Never use tab characters to indent your blocks, only spaces. You can – and should – configure your editor to put 4 spaces when you press the tab key. The problem with using tab characters is that other python programmers use spaces, and if both are used in the same file python will read it wrong (in the best place, it will complain, and in the worst case, weird, hard to debug bugs will happen).

A function for a square¶

Exercise¶

Write a function that draws a square. Could you use this function to improve the tilted squares program? If you change the program to use a function, is it easier to experiment with?

Solution¶

def tilted_square():

turtle.left(20) # now we can change the angle only here

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

tilted_square()

tilted_square()

tilted_square()

# bonus: you could have a separate function for drawing a square,

# which might be useful later:

def square():

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(90)

def tilted_square():

turtle.left(20)

square()

# etc'

Comments¶

In the solution above, the line that starts with a # is called a comment. In Python, anything that goes on a line after # is ignored by the computer. Use comments to explain what your program does, without changing the behaviour for the computer.

Comments can also go at the end of a line, like this:

turtle.left(20) # now we can change the angle only here

A function for a hexagon¶

Exercise¶

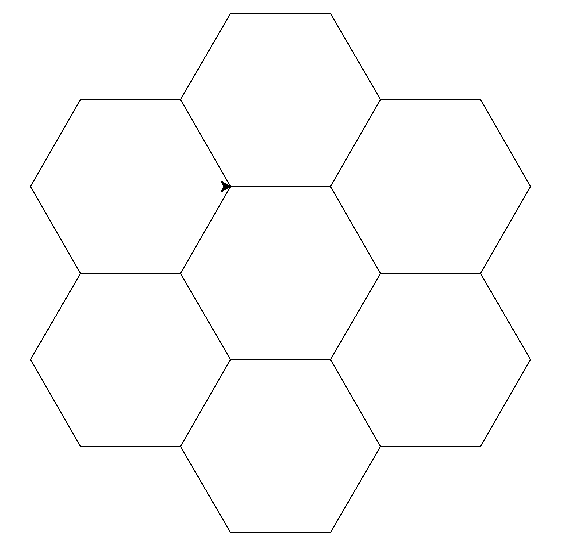

Write a function that draws a hexagon.

Now combine that function into a honeycomb. Just make it with a single layer like this:

Solution¶

def hexagon():

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.left(60)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.left(60)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.left(60)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.left(60)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.left(60)

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.left(60)

hexagon()

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(60)

hexagon()

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(60)

hexagon()

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(60)

hexagon()

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(60)

hexagon()

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(60)

hexagon()

turtle.forward(100)

turtle.right(60)

You could also put the turtle.forward(100); turtle.right(60) portion in the function, but you better not call it hexagon in that case. That’s misleading because it actually draws a hexagon and then advances to a position where another hexagon would make sense in order to draw a honeycomb. If you ever wanted to reuse your hexagon function outside of honeycombs, that would be confusing.